Key Information

Name: Archie Ronald Kerr

DoB: 27/01/1921

Regt:

DoD: 20/11/1940 19

Buried/Commemorated: CARLISLE (DALSTON ROAD) CEMETERY

Academic Career: CS 1932-36

Other:

Biographical Information

-

Family Background:

Son of Robert Gilmour/Gilmore Kerr and Margaret Jamieson Kerr, of Long Sowerby, Carlisle.

1932 27, Lorne Crescent.

10 Well Bank Carlisle (1940)

-

Academic Record

Moved from Fauld House Public School, West Lothian.

CS 1932-36.

-

War Service:

Pilot Officer Navigator?Air Gunner

79182, 44 Sqdn., Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

Information below f\rom James Mindham:

Crew of Handley Page Hampden X3023 44 Squadron

KERR, ARCHIE RONALD (KILLED)

Rank: Pilot Officer

Trade: Nav./Air Gnr.

Service No:79182

Age:19

Regiment/Service: Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

OTTAWAY, JACK LEONARD FREDERICK (KILLED)

Rank: Sergeant

Trade: Pilot

Service No:528798

Age:25

Regiment/Service: Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

ELLIOTT, STANLEY FREDERICK (KILLED)

Rank: Sergeant

Trade: W. Op.

Service No:935731

Age:21

Regiment/Service: Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

HIRD, STANLEY (INJURED)

Rank: Sergeant (Later Flying Officer DFC Service Number 155876)

Trade: Gunner

Age:21

Regiment/Service: Royal Air Force Volunteer ReserveThe fate of Handley Page Hampden X3023

The following account is a best guess based on the available evidence, I have also drawn upon many

sources relating specifically to the Handley Page Hampden and many hours of trying to relive the

situation in my mind and understand what the crew of X3023 were facing and decisions that were

made. Assistance has also been given from the Handley Hampden Restoration Project as Cosford, The

Royal Armouries and a ballistics expert.

Jack Ottaway, Archie Kerr, Stan Elliott and Stan Hird climbed aboard their brand new aircraft and at

quarter past one in the morning of the 20th, Handley Page Hampden, registration number X3023,

struggled into the overcast alone and on her first operational trip, it would remain alone throughout

the next 5 hours as a course was set for the enemy coast.

The target that night was the oil refinery at Lutzkendorf, deep into Germany. This distance was at the

extreme range of the Hampden and the crew of X3023 would suffer in the cramped and cold

conditions for next 10 hours.

Earlier in the year, several Hampdens were forced to ditch or crash land as their engines spluttered

and choked as the fuel ran out. Jack’s navigator this night was Archie Kerr, who survived a well

documented ditching off Lowestoft in the summer, also Jack’s bottom gunner (Stan Hird) crashed Stan recovered from his injuries and survived the war, one of the very lucky ones who saw out the

entire conflict as bomber crew. He was awarded the DFC.

As X3023 reached out across the North Sea, it would have been vital that Jack and his crew knew

where they were crossing the enemy coast. The wind was incredibly strong, blowing from the south

west and pushing X3023 further north east all the time. Cloud cover and mist would have meant that

Archie could not possibly know where they were unless they got a visual fix. The moon was

approaching its last quarter, so there would be light enough if there was a break in the clouds.

It is possible that Jack flew low and under the cloud cover so that they could at least try and find out

where they were as they approached the Dutch coast. A quick calculation based on other aircraft take

off and arrival times that night, suggests that X3023 could not have got very far inland before they ran

into trouble.

The accident report card (Form 1180) suggests that the X3023 was engaged in a ‘Flying Battle’ (FB)

and a fire-extinguisher component found at the crash site shows two bullet strikes, the calibre was

either British .303 or German 7mm. Form 1180 also states that the starboard engine had failed –

presumably as a result of being attacked as E/F (FB) (Engine Failure (Flying Battle)) is written.

The question remains, who actually fired at X3023? Currently there are no records indicating that the

Luftwaffe were operating that night, this may change in the fullness of time, but to me it seems

unlikely that X3023 was attacked by a German night fighter. I think that if the night fighter was close

enough to land tightly spaced machine gun bullets into X3023, then its cannon fire would have torn

the Hampden to pieces resulting in an immediate crash.

Another possibility is that this was friendly fire and that X3023 chanced upon another bomber making

its way across the North Sea and was fired upon, although at the present time there is no indication

that other RAF aircraft were on a converging course – this may change with more research and further

analysis of take-off times. Incidentally, another co-incidence that night was the disappearance of

Hampden X3024 – the aircraft that followed X3023 off the production line. This Hampden and crew

was lost over the North Sea a few hours after X3023 crashed for reasons unknown.

Was X3023 low enough to be engaged by ground machine gun fire? This seems more likely as it never

gained altitude and was never going to do so with one engine, so it had to be low in the first place. It

seems reasonable to assume that the engine failure occurred soon after X3023 was hit as Jack took

the decision to return.

The only way the investigators would have known about the starboard engine failure was either the

account from Stan Hird or via a radio message. There is a tantalising hint that a radio message was

made from X3023 as something that looks like ‘wireless call’ can be seen written on the Form 1180.

Flying the Hampden on one engine was incredibly risky, many crews did not take the chance of landing

on one engine and if they had the height, they would bail-out. 27 Hampdens were abandoned by theircrews on return from operations and I think this would have been the best and only option for Jack

and his crew –the trouble was that they never had sufficient height in the first place.

“In addition to providing an awesome spectacle, the sudden loss of power from an engine necessitated

prompt action from the pilot to maintain control of the aircraft and prevent it rolling over onto its back

and going into a spin from which recovery would almost be impossible.” –

Harry Moyle (The Hampden File)

It cannot be overstated just what a gargantuan task it would have been to fly X3023 back across the

North Sea on one engine.

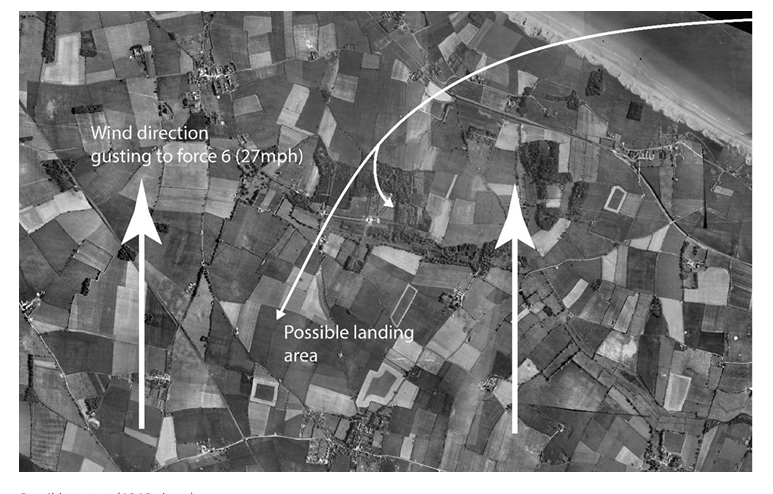

The wind was blowing directly across him – sometimes gusting to over 25mph, as he struggled back

home across the angry waves. The torque of the port engine would have dragged him to starboard

with the wind exacerbating the effect, so the whole aircraft would be yawing to starboard and further

out into the North Sea. Jack would have needed considerable physical strength to crab the aircraft

into the wind using his ailerons and a ‘bootful’ of left rudder.

Maybe Jack was aware of the fundamental flaw in the Hampden design which would catch out less

able flyers. The small rudders of the Hampden would sometimes lock over if the aircraft made a

shallow turn, in other words if the bank angle was low during a skiddy turn, the rudders would lock,

the controls become useless and the aircraft would stall or flip over – this was known as ‘the stabilised

yaw’. In rare cases of survival, recovery was made by the clever use of the throttles on both engines

and having altitude. Jack had neither.

Harry Moyle dedicated a chapter to the issue of the stabilised yaw in his book – ‘The Hampden file’.

“There were more enquiries after L4128 crashed at Hemswell on the 2nd June 1939 when attempting

to land on one engine and one of the questions put to Squadron Leader Stainforth was, ‘Is the effort

needed to fly straight on one engine such that a small or comparatively weakly pilot might be expected

to lose control in a very short time?’ His answer was ‘Yes’.” –

Harry Moyle (The Hampden File)

Quite how Jack managed to fly for so long in conditions so conducive for the stabilised yaw is quite

astonishing.

Another item recovered from the crash site was the landing lamp dipping lever. This was set and

locked to a fully forward position which suggests that the lamp on and set to the reconnaissance

position thus enabling Jack and Archie to observe what they were flying over. It is possible that the

final forward position of the lamp was a result of the crash, but I think it is unlikely as the lever requires

a specific sequence of movements to attain the forward position. Firstly, the ratchet lever needs to be

disengaged and then pushed against the dipping lever so that both levers are moved simultaneously

in a clockwise position and then rotated through 90 degrees from the normal position.

Jack may have had the hood open to observe the terrain or sea – maybe he was assessing his height

or considering ditching, but ditching would have meant certain death, and I cannot believe Jack

considered it as a realistic option.

The starboard engine powers the hydraulics and electrical accumulator, so with the starboard engine

gone, these systems would also fail. It meant that power to the battery was lost and power needed

for the landing lamp. Just how much power the battery would have retained after it was no longer

charging is unknown. The engine failure also rules out any controlled landing, although the wheels could be dropped by

using the emergency compressed air option, he would have no flaps and landing with one engine even

in benign conditions was considered too risky by most.

By an amazing feat of flying and navigation, X3023 made landfall just before 6.30am. The relief would

have been palpable, and I sure that making the coast would have been the only immediate concern

for Jack since choosing to return to England, but the reality of the situation would have been stark.

Without height their chances of survival were negligible. Squalls were present and the wind and rain

were constantly pushing the aircraft in the wrong direction, Jack would have barely been able to keep

the aircraft flying and bailing out was not an option as he never could get the height. A desperate, gut

wrenching feeling.

At 6.30am, Jack lost the fight and X3023 crashed in a clearing a few yards from the gamekeeper’s

cottage at Templewood, Northrepps. Form 1180 suggests that Jack lost control of the aircraft due to

the ‘excessive’ weather conditions and flying on one engine. This is probably true and was probably

inevitable, but Stan Hird survived and was cared for by the gamekeeper Fred Gray and his wife Lottie.

Both were woken by the crash and dashed outside to see him stagger about silhouetted by the flames.

Shaken and confused, Stan thought he had crash landed in Poland as he found the Norfolk dialect to

be quite foreign to his ears.

Was Jack attempting to crash land X3023? It’s possible. He would have been exhausted, maybe even

injured, and probably put all his strength into making it back to England and taking his chances – there

simply were no other options.

I don’t think we can underestimate the importance of finding the landing lamp dipping lever as it

suggests that the lamp was on and that Jack had chosen to crash land.

The weather records from RAF Coltishall show that between 6am and 7 am, the cloud cover changed

from a complete coverage at 5000ft to four tenths coverage at 1000ft with a visibility of 4 miles.

Crucially the moon was high in the south west and three quarters full, it is entirely possible that Jack

could see an opportunity in the moonlight.

A mile or so to the south of the crash site, there are large, open and flat fields on the high ground to

the east of Southrepps. During the following years, several stricken USAAF bombers crash landed in

this area, one of which made a successful wheels up landing, so getting an aircraft down there would

not be unprecedented.

After landfall, Jack would have turned to port towards his good engine, in the moonlight he may have

been able to distinguish woodland from field and hedgerow and picked a spot as he turned into the

wind. The probability is that he finally lost control just short of a miracle.

The gusting wind from the south was in the region of 25-30mph. So after being used to a buffeting

crosswind for the journey across the North Sea, Jack turned the aircraft into an unpredictable

headwind which would have created a fair degree of turbulence as it was deflected up and over the

higher ground and trees of the Mun valley into which he crashed.

Any turn in those circumstances was incredibly risky in the circumstances, the slightest buffeting from

the wrong direction, a crucial loss of airspeed or perilous change in attitude could easily lead to the

stabilised yaw. Judging from documented examples, it is likely that the Hampden suddenly became

nose heavy, rolled and crashed from a low altitude. X3023 rediscovered

I first heard of a WW2 plane crash at Templewood back in the late 1980s, when Major Anthony Gurney

told me that he was sent up to the crash site to help with the recovery. I’m sure that he said that it

was a Whitley Bomber, it stuck in my mind because as a boy I was endlessly fascinated by bombers of

World War Two.

Having spent many years field walking and metal detecting in the area for archaeological research, I

decided to see whether I could find anything related to the plane crash which was now only vague

story. Major Gurney told Eddie Anderson (the landowner) that the aircraft lay across the trackway to

the game keeper’s cottage, so I started to look on a grassy area to the right of the track.

Within minutes I was picking up signals and recovered degrade aluminium and signs of burning. The

odd small component was found, but most intriguing of all was that all the signals and finds where

occurring in two parallel lines. It was then that I decided to dig a small archaeological evaluation trench

to find out why.

Eventually the reason why the wreckage was being found in parallel lines became clear. The site has

essentially been untouched since that fateful day, and to my astonishment I had uncovered the wheel

ruts of the recovery vehicle which had got very stuck in the sodden ground. The wheel ruts were very

deep and I even found wood and bricks that were propped either side of the wheels to try and help

the tyres get purchase. Also a very rotten, but recognisable strop was found that was laid along one

of the ruts, again, in order to help the tyres grip.

After the vehicle had left the scene, the wheel ruts were backfilled with burnt debris and small

fragments of wreckage and then smoothed over. It’s amazing to think that although representing an

incredibly small percentage of the aircraft, the fire extinguisher component with bullet holes and the

landing lamp dipping lever were found in the backfill. Without these, the story of X3023 would have

been consigned to history and even more speculation.

In terms of pinpointing the impact and debris zones, the only archaeological evidence we have is a

small areas of burning that the recovery vehicle drove over. Rather than debris being used to backfill

a wheel rut, these areas show clearly that the wheels ran over burning and wreckage before getting.

A large slab of melted aluminium found within the tracks is testament to the ferocity of the fire.

As a twelve year old boy, Ted Bird from Southrepps, cycled to the crash site 3 days afterwards and

noted a large area of burning on the high ground in front of the cottage, and Alan Woodhouse (current

resident of the cottage) was told that there was wreckage and burning by the bank separating the

wood from the clearing. If true, then this demonstrates a west to east impact and debris trail. At this

time I have not found any evidence of the crash other than from within the wheel ruts, and these ruts

themselves give us some positional clue as the vehicle that made them must have been coming from

an area of wreckage and back onto the track.

Major Gurney also mentioned that a tree next to the gateway of the cottage was destroyed in the

crash. This tree and the others that lined the track, would have been only a few years old – nothing

more than whippy sticks and it hard to believe that other saplings where not destroyed during the

crash. The 1946 aerial photograph shows no gaps in the tree avenues, other than a potential gap near

the gateway where such a sapling was destroyed according to Major Gurney. -

Other:

Left school to join the Opticians, Devonshire Street.

Gravestone inscription: “He died that we might live”

-

Sources:

The Creighton Register

James Mindham